WHO WAS MELVIN VAN PEEBLES?

The Godfather of Black cinema. A one-man revolution. The coolest person you’ve ever heard of.

Director. Writer. Actor. Producer. Playwrite. Novelist. Musician. Composer. Painter. Uncompromising Black visionary. Blaxploitation pioneer.

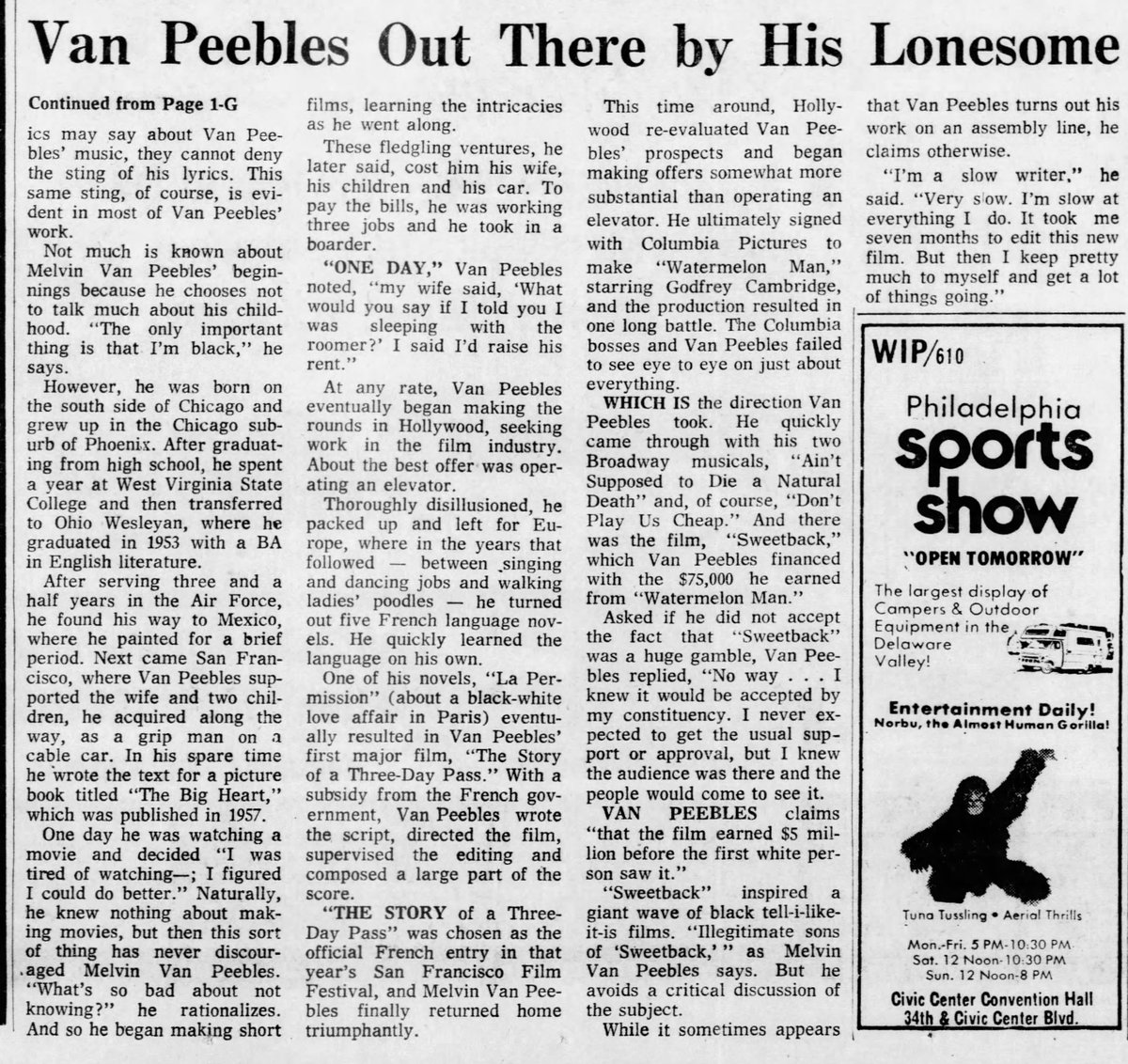

Van Peebles started his filmmaking journey while working as a cablecar operator in San Francisco. There he directed a few short films, including "Sunlight" (1957), before taking his talents to France to pursue an astronomy Ph.D. after being unable to break into Hollywood. While in France, he decided he was going to make it as a director or die trying. His journey to making it as a feature film director included writing five books in French, street performing, acting, dancing, and numerous odd jobs. After learning he could adapt one of his novels, La Permission, into a film with funding from the French government, his dreams of being a feature film director were realized with "The Story of a Three Day Pass" or "La Permission" (1967).

"Three Day Pass" is an edgy romance that tells the story of a Black American soldier stationed in France granted a three-day leave. He heads to Paris and falls in love with a white Parisian woman. The film explores the lived complexities of institutional racism and romance with French New Wave style.

"The Story of a Three Day Pass" gave Van Peebles access to his Hollywood dreams once denied. In 1969, he entered into a contract with Columbia Pictures and made his only foray into Hollywood filmmaking: "Watermelon Man." (1970).

Often relegated to a footnote in general conversation regarding Melvin Van Peebles' work, "Watermelon Man" (1970) is simply one of the most essential films in Black film history. “Watermelon Man” tells the story of Jeff Gerber, a white supremacist suburbanite who inexplicably wakes up Black overnight. With this film—released in a moment of growing civil unrest in the United States—Van Peebles crafts one of the most radical films in Hollywood history, serving as director, composer, and a point of refusal to the studio's anti-Black demands as they proposed to have a white actor in blackface and gentler ending.

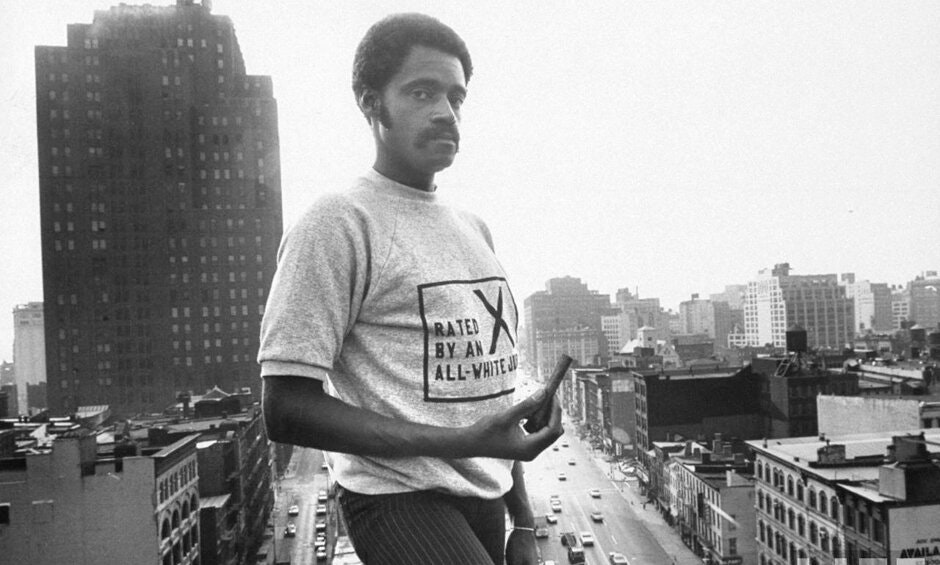

"Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song" is possible because "Watermelon Man" exists as Van Peebles used his salary from the latter to fund "Sweetback" after walking away from his Columbia Pictures contract. Rated X by an all-white jury, "Sweetback" created a prototype of Black imagery through the story of a Black sex worker who becomes a Black Power revolutionary after a run-in with cops. This landmark independent film was produced, written, directed, starring, edited, and composed by Van Peebles.

Following the success of "Sweetback," Van Peebles turned his attention to Broadway as an additional tool in his arsenal of telling rich stories about Black life. Producing two critically lauded and Tony-nominated musicals, "Ain't Supposed to Die a Natural Death" and "Don't Play Us Cheap," the latter becoming his next feature film in 1972. In the late 70s, he also wrote an additional novel called The True American, which he turned into a TV movie, "Just an Old Sweet Song."

Van Peebles continued to act, write new works across mediums, and support his son Mario's blossoming career as an actor, director, and ultimately his co-collaborator as the 70s made way for the Black independent film boom of the 1980s and 1990s.

In an unparalleled career and through his many artistic forms, the Godfather of Black cinema made an immortal mark still felt today.

Read More ︎︎︎

Van Peebles continued to act, write new works across mediums, and support his son Mario's blossoming career as an actor, director, and ultimately his co-collaborator as the 70s made way for the Black independent film boom of the 1980s and 1990s.

In an unparalleled career and through his many artistic forms, the Godfather of Black cinema made an immortal mark still felt today.

Read More ︎︎︎

In 2010, Melvin Van Peebles was preparing for the Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song stageplay. This clip offers a look at the director’s process.

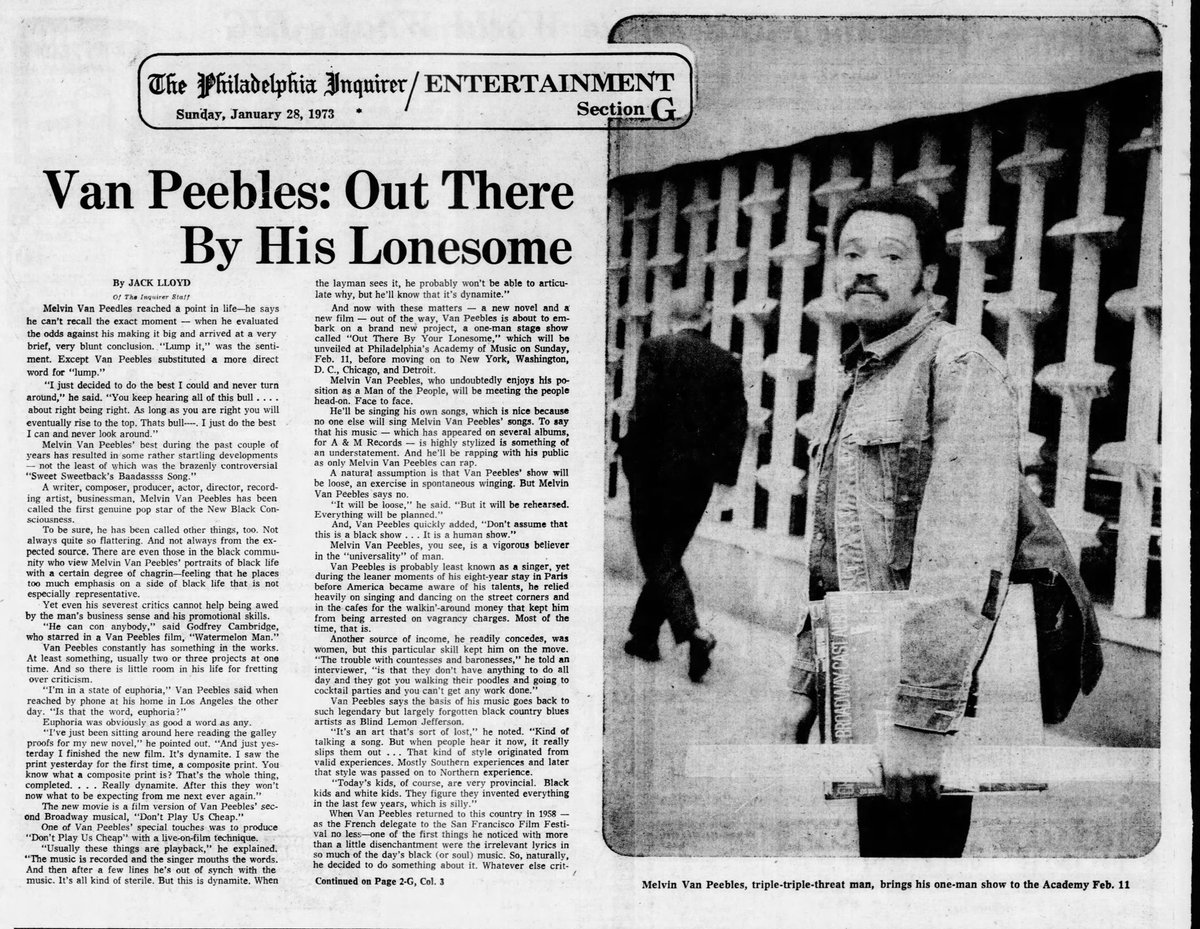

June 1973 Melvin Van Peebles interview in Essence Magazine. Special thanks to photographer and archivist Silas Vassar, III for scanning this in for Black Film Archive.